Technical Language In The Mainstream

examining the popularization of clinical and academic terms

Again, adapted from a research paper for class—I promise I originally came up with the idea for an article! Much inspiration from

and their piece Do Words Mean Anything Anymore? which I reference all the time. Please check it out!!Words and their meanings easily change over time to suit current trends and their needs. Technical language often gains popularity for the purposes of ease, being able to define a condition or experience in a single term.

Yet, mainstream adoption also comes with a dilution of meaning. Increasingly, people have begun to define themselves in ways that make them more easily consumable, specifically through clinical and radical terms, which were not originally meant to be used so flippantly. Through clinical language, pathologization occurs, in which experiences are watered down to the point that normal symptoms are viewed as extremes. This shallow usage extends to radical language, where terms end up serving the very things they originally critiqued.

Clinical Diagnoses and Experiences

By unnecessarily and excessively using clinical terms, people who need the specificity find themselves without the right language. Ignoring original meanings and “overapplying” terms “dilute[s] its meaning” (Waldman). As The New Yorker’s culture writer Katy Waldman explains, it robs “people who have experienced legitimate trauma of language that is already oftentimes too thin” (Waldman). Furthermore, “invoking ‘trauma’ where ‘harm’ might suffice” could downplay genuine vulnerability that comes from the initial, intended labels (Waldman).

Therapy-Speak’s Dilution of Meaning

Oversaturating clinical terms fails to normalize their conditions, rather, average conditions are made even harsher in comparison. This new, seemingly ever-constant usage of diagnoses has been dubbed “therapy-speak” or “pop psychology” (Volpe). Many of the people who are able to participate in therapy are already privileged in many ways–though foremost in their access to therapy in the first place (see image). With that in mind, therapy-speak turns into a “class confession” where the words “suggest a sort of woke posturing, a theatrical deference to norms of kindness, and they also show how the language of suffering often finds its way into the mouths of those who suffer least” (Waldman). This utilization does nothing but make the terms banal, in usage by people who misconstrue the very concept or experiences behind them initially.

Take “O.C.D.”—a diagnosis including a “pattern of unwanted thoughts and fears known as obsessions [...] that lead to repetitive behaviors” yet, in mainstream usage, rarely are instances actually obsessive-compulsive, it has begun to simply mean overly organized in an abnormal way (“OCD”). Instead of creating awareness towards them, symptoms such as intrusive thoughts similarly become adulterated and ultimately a “[disservice to] people with severe mental illness” (Waldman). Intrusive thoughts have turned from the often taboo “unwanted and repetitive thoughts, images, or urges” to examples akin to ones found by TIME Magazine’s health and wellness editor Angela Haupt on TikTok about a “quick thought about whether you should jump on stage as your favorite band” (Haupt). As cultural critic and large inspiration for this paper, Charlie Squire, said, “Not only have we failed to normalize the most uncomfortable aspects of mental illness, but we have actively othered them” (Squire). More intense symptoms are glossed over in favor of watered down, average, experiences, as opposed to specificity.

Radical Terms and Ideologies Behind Them

Living in a post-pandemic world, people have begun to feel less connected to the real world, and instead find it within the online world and the trends/terminology that come from it. This online connection can lead to inauthencity that extends to usage of popularized radical language. Marketing lecturer at the University of London and co-author of a study following the “self” under COVID-19, Jingshi Liu affirmed in an interview with TIME Magazine, “people would feel most inauthentic when they are performing to others in a way that is inconsistent with how they are [thinking and feeling internally]” (Dutta). By defining themselves through trends without regard for meaning, people, in turn, feed into systems in which the words were meant to be foils to.

Formed From a Critical Stance

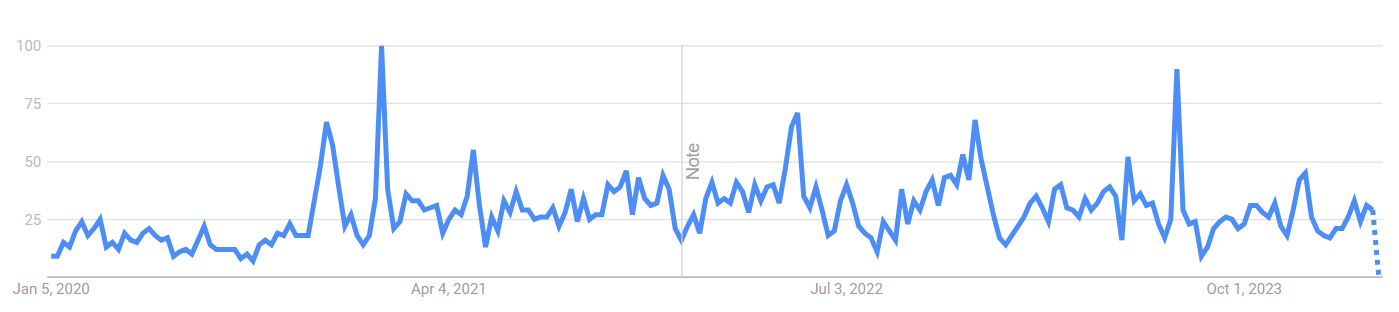

Radical terms such as “male gaze” carefully exist to critique the current cultural landscape but have become simplified to the point of inhibiting discussion. “Male gaze” was first described by art historian and critic John Berger to delineate the internal surveillance women feel about the way they are perceived, particularly by men and female portrayal within art. Berger details in his 1972 novel Ways of Seeing, “men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at” (Berger 47). This usage of “male gaze” has seen major upticks in usage (see image below), with this popularization, the term has been rendered down to simply what men like, or, the “tastes of men, and specifically a 1950s, Americana taste” (Squire). This is opposite from the carefully described phenomenon born from the patriarchy. Of course, with the popularity of this definition of the male gaze, there is an attempt to subvert it–appeal to the “female gaze” (Silva). However, it is often forgotten that subversion is part of the fantasy itself: you can not escape the male gaze. By using a circular understanding of such terms, criticism of the systems around us fails.

Inversely, the Bechdel Test, started as a joke, gets conflated to being a genuine standard to view films with. The test, named after queer cartoonist Alison Bechdel, was created as “a little lesbian joke in an alternative feminist newspaper” and assesses if two (named) female characters have a conversation about something other than a man (Morlan). Bechdel herself “didn’t ever intend for it to be the real gauge it has become” (Anderson). Though its popularity rings ironic to the creator, the Bechdel test has shed light that even a simple test of even vague female involvement is too much to ask for from much of film and media. The Bechdel Test serves as a near-exception where conversations built from specific language grow even more nuanced than intended.

Inadvertent Approval of Online Extremists

While radical language is rooted in criticism of culture, that does not mean that all iterations end up positive. Instances include how involuntary celibate (incel) practices and terms have been established in outside online communities as a joke, or even practical application. “Looksmaxxing” for example, is a common knowledge to the vaguely online, one of constantly improving one’s’ looks towards perfection (Rosdahl). What is less known, is the extent to which these unhealthy or dangerous standards are being geared to. Primarily young men are the focus of the trend, many finding idolization within Patrick Bateman–the fictionalized serial killer from Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho–for his seeming “perfection” (Rosdahl). Senior Lecturer at the Australian College of Applied Psychology Jamilla Rosdahl explains that when “young people feel like they can’t control their environment, they may turn to trends such as looksmaxxing as something they can control” (Rosdahl). At its core, looksmaxxing has its ties to phrenology, a pseudoscience that suggests the size of one’s skull genuinely suggests higher intelligence, a notion adopted by many incels and the like. Even if looksmaxxing, on a surface level, appears to be harmless, further investigation into it can easily lead into a particularly dangerous extremist rabbit hole. In fact, the popularization of incel culture has led experts to be weary towards growing terrorism as a result of the toxicity within its online forums (Townsend). When radical terms have their start in harm, popularization can lead to even more harm, where people disregard or are not even aware of their origins.

Conclusion

Technical language becoming popularized has many major impacts including diluting clinical terms, critical terms losing their impact, and extremist vernacular leading to harm. With clinical language, people who need precise language without being viewed as extremes of a condition are left with weak terms, made through generalization. Correspondingly, radical phrases stemming from criticism become useless against systems, and in fact can turn into support of the aforementioned systems. Extremist terms–an even more radical, perhaps too radical, offshoot of critical language–becoming mainstream can lead to younger, more online generations falling into hellacious communities. People must be careful with the words they use, for they help contextualize the world around us. If those terms are misunderstood or become useless, people have nothing left to acutely describe anything with.

(The formatting is vaguely MLA, I’m aware it’s not exact, for that wouldn’t have translated the best to Substack) If you enjoyed this article, please be sure to share with whoever you feel like would be interested the most in this topic!! Or your local band's bassist, purple-lover, or most diligent note-taker. - Alaïa <3

References

Anderson, Hephzibah. “Alison Bechdel: ‘The Bechdel test was a joke... I didn’t intend for it to become a real gauge’.”

Berger, John, et al. Ways of Seeing.

Dutta, Nayantara. “4 Ways That the Pandemic Changed How We See Ourselves.”

Haupt, Angela. “What It Really Means to Have Intrusive Thoughts.”

Morlan, Kinsee. “Comic-Con vs. the Bechdel Test.”

“Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD).” Mayo Clinic

Rosdahl, Jamilla. “‘Looksmaxxing’ is the Disturbing TikTok Trend Turning Young Men Into Incels.”

Silva, Christianna. “In the Age of TikTok, the Female Gaze Has Lost All Meaning.”

Squire, Charlie. “Do Words Mean Anything Anymore?”

Townsend, Mark. “Experts Fear Rising Global ‘Incel’ Culture Could Provoke Terrorism.”

Volpe, Allie. “The Limits of Therapy-Speak.”

Waldman, Katy. “The Rise of Therapy-Speak.”

Further Reading

April Dembosky - “How Therapy Became A Hobby Of The Wealthy, Out Of Reach For Those In Need”

Sukhdev Sandu - “Ways of Seeing Opened Our Eyes to Visual Culture”

James Bridle - “New Ways of Seeing: Can John Berger’s Classic Decode Our Baffling Digital Age?”