To Make a Woman: Subway Girl & 'The Second Sex'

TikTok’s controversial ‘Subway Girl’ has taken the world by storm, but what does her take really say about how women are perceived in media, and how it extends into daily life?

Now more than ever, people are beginning to examine the ways in which women are cyclically categorized. Constantly, there is the ask of what women should be–chill, nurturing, casual, toxic, even. All stemming from men projecting their ideal women onto others. This occurrence presents itself in everyday life, but through media is only bolstered more into public attention. On TikTok, ideas and standards are easily spread. And in traditional film, well respected directors are praised for their simple usage and tokenization of women. Which, of course, bleeds into the personal lives of everyday people. Men who grow up to marry, have children, still manage to project these standards of what women should be onto their wives and children. The dynamic is especially strong between father and daughter. As Asisa will later examine, their bond is much more of mutual respect than that of the husband and wife.

This phenomenon then poses the questions: Are we not larger than this? Larger than the ways in which we have been boxed in, defined by men? And is the failure of to see each other as real, material people not a concern?

Who / What Exactly Is The ‘Candid Girlfriend’?

Amongst all niche, micro-types of girls that have surfaced in our modern media stream, none seem to have sparked as much incisive conversation as the “candid girl.” On March 31st, @subwaytakes on TikTok posted a viral video featuring New York comedian Stef Dag dishing out her hottest take: the boxed-in ways in which men “make a muse” out of the women they pursue. Dag explains that men don’t want the “cool girl” (à la Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl) that’s stark, edgy, complicated, and to a degree difficult–they want the “candid girl.” Naturally waifish girls with “mousy brown hair, no longer than shoulder length,” a mildly interesting upbringing, and a love for pomegranates. In short, and in comparison to the cool girl: effortlessly plain, with a spark, moldable.

Of course, male fantasies and their projections are nothing new, in fact, candid girls seem to be a mirror of the long-lasting Manic Pixie Dream Girl, the originally film archetype that bled into the mainstream to the point of aspiration. Coined by film critic Nathan Rabin, the manic pixie dream girl (MPDG) exists largely to “teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures.” MPDG can be characterized by whimsy, niche indie rock bands, and being short-lived. Popular examples include Ramona Flowers in Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World, Summer in 500 Days of Summer, and naturally, the original Claire in Elizabethtown.

Curiously enough, the MPDG largely consists of white women. In the peak of its usage, the 2010 “film bros” that were indulging in this fun-loving, waifish, and niche caricature did not include any women of color. Further pushing the narrative that they are undesirable, not able to see themselves in these easily loveable women, made muses in films. The distance from women of color feeds into another issue–where they are either alienated or fetishized.

East Asian women in particular were made to feed into orientalist stereotypes, such as in the 1931 film Daughter of the Dragon, directed by Lloyd Corrigan. The female lead, Anna May Wong, was the first main, Chinese actress in Hollywood, and yet, for her role in Daughter of the Dragon, she was paid less than half of her white male co-star, Warner Oland. As Teen Vogue culture writer India Roby writes, these types of films “minimized Asian women by portraying them as seductive yet disposable bodies.” No matter the ethnicity, women in media and the mainstream will still be made into simply objects of desire, devices in which men can better themselves with and promptly cast away.

Why the Internet Hates ‘Subway Girl’

Whilst there are those who merely reduce ‘Subway Girl’ for being associated with the commonly acknowledged ‘Pick Me’ girl archetype, the truth is that most people critiquing her aren’t necessarily missing her point. To many of us it’s somewhat clear she’s outlining the ways in which the “Candid Girlfriend” is only perceived as such through the eyes of a self-centered and largely uninterested boyfriend. But in reality her critique of him falls short as she misses him in her monologue and hits “Candid Girlfriend” who is at the very worst only guilty of accepting love from a man who doesn’t fully see her. Instead ‘Subway Girl’ critiques her plainness listing traits that seem to be painting her as the commonly mocked, simplistic and boring ‘girl next door,’ in contrast with the fiery and complex Cool Girl archetype with ‘Baby bangs and a bad father.’

Despite the fact that this may not have been her intention, the language she uses and the way in which she centers the woman here ultimately frames this as just another critique of women in a social context where we’re not short of these critiques. She calls the ‘candid girlfriend’ empty headed instead of saying the man assumes she has nothing going on in her head for example. She never references the kind of man who does this, instead goes into extraneous detail about the woman he’s controlling. Content creator Komi or ‘Not Wildin’ likened her failed critique with a similar perspective operating within the black community. Where racial ‘sell outs’ have been long mocked* for their pandering to whiteness, many miss the abuse of power enacted by their white counterparts. Instead of saying “Look at the abuse perpetuated by white people on their black peers” we say “Look at the coon exchanging his pride for white approval.” Even if our black person should be criticized for the ways in which his behaviour is detrimental to racial objectives for equality, in the same way that “Candid Girlfriend” might potentially set back feminist objectives with her male centric approach, Komi argues we’re too often separating the perpetrator of oppressive actions* with said actions. In this case, the boyfriend in question is the one reducing his girlfriend to a small set of meaningless* characteristics, and yet we exacerbate this by perceiving her through his eyes whilst critiquing her lack of strength.

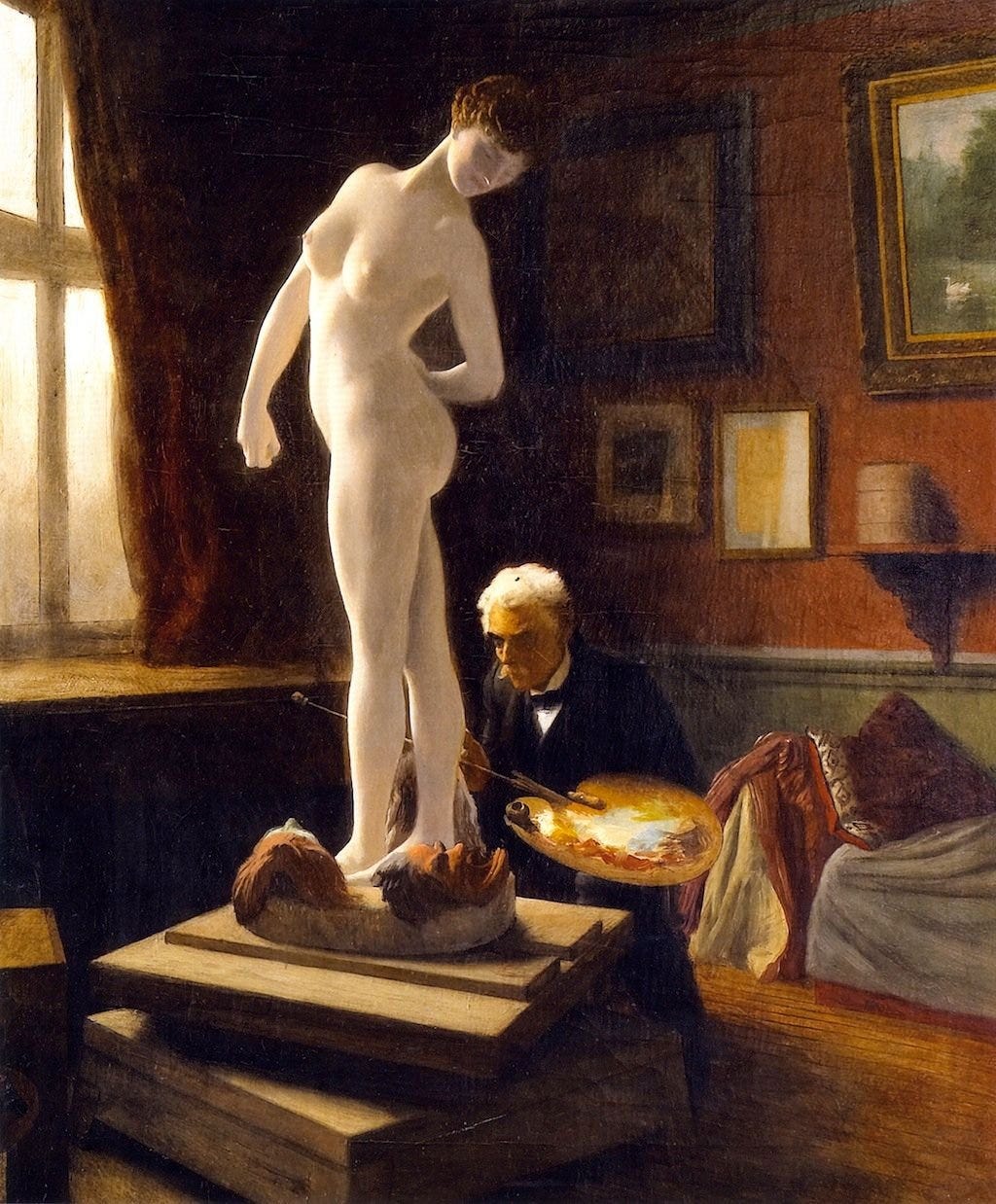

It’s an all-too-common phenomenon, where men with lives ‘too full’ for a completely whole companion undertake the task of make a muse out of her. In the same way that the artist, wanting to impress his personality onto the object of his creativity, wants to begin first with a blank canvas, men are seen to require women of a similar yet entirely perceived bland candidness. Onto her they can successfully impose their own values, aspirations and aesthetic, so that like the artist’s painting, she embodies him.

The Muse

But what does it mean to ‘Make a Woman?’ De Beauvoir explores this concept in depth in ‘The Second Sex’ (1949), where she notes women are often objectified as muses by men, a theme that has been common throughout history and literature. The idea of a muse traditionally comes from Greek mythology, where muses were goddesses who inspired artists, poets, and thinkers. However, in the context of De Beauvoir's analysis, men often seek to make women into muses in a more objectified and subordinated sense.

One commonality is the portrayal of women as passive objects of male desire and creativity. Throughout history, women have frequently been depicted as sources of inspiration for men, but this inspiration often comes at the cost of women's autonomy and agency. Women are unknowingly cast in the role of muse, expected to inspire and uplift men's artistic or intellectual pursuits, but without any agency or voice of their own. As we’ve seen empirically, this phenomenon reflects broader power dynamics between men and women in society. By positioning women as muses, men assert their dominance and control. As women are reduced to objects of male desire and imagination, reinforcing traditional gender roles and perpetuating inequality. Additionally, the concept of making a muse out of women reflects the objectification and commodification of women's bodies and identities. Women are often valued solely for their physical appearance or perceived ability to inspire men, rather than for their intellect, talents, or individuality, which explains ‘Subway Girl’s’ assertion that the ‘Candid Girlfriend’ has nothing going on upstairs.

And yet, the process of ‘making a woman’ doesn’t begin by merely observing that she is plain. First, he might in vampirish fashion drain her, proceeding to mimic her core personality traits, and suddenly he’s presented as the kind of man who understands women, when really he has embodied his own. But of course, he is entirely unaware of his part to play here, and wearing the outfit she inspired, dares to assume her ‘plainness’.

“...her wings are cut and then she is blamed for not knowing how to fly.”

― Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex

Pearl’s Ineffectiveness

Seeking male approval, whether intentional or not, can find itself on both sides of the political spectrum. One would think that to conservative men, Hannah Pearl Davis (better known as Pearl) is a dream. After all, she is extremely vocal about upholding traditional values on what a woman should be. Dubbed the “female Andrew Tate,” some of her ideas include the repeal of the 19th amendment (the one that states no one should be barred from voting due to their sex aka the one that allowed women to vote) and despite not being married or having kids, pushing the notion that all women are happier with the traditional household style over a career.

Pearl rallies hate against women in the effort of appeasing men, yet manages to do the exact opposite, marked by her short-lived relevance. Instead of seeing her actions as in line with their own beliefs, Pearl is seen as too outspoken. Not only that, but Pearl has an audience (nearly 2 million on YouTube, over 425k on Twitter / X), meaning she has power the majority of the men she is catering to do not. The men in question would rather “domesticate” a radical woman and make a republican out of her, exerting power over her instead of someone exuberantly in tandem with their ideologies.

Male Projection

The male gaze (a term endlessly analyzed now) is reliant on insecure men needing to feel dominant. There have grown to be many variations on what women are “supposed” to be as opposed to one universally agreed upon idea, men project their individual needs and wants onto the women they pursue. The idealized woman is largely reliant on men, and overall women have little to no say in how they are perceived, at least initially, they just know they are.

As Gillian Flynn monologues in Gone Girl:

“Men always say that as the defining compliment, don’t they? She’s a cool girl. Being the Cool Girl means I am a hot, brilliant, funny woman who adores football, poker, dirty jokes, and burping, who plays video games, drinks cheap beer, loves threesomes and anal sex, and jams hot dogs and hamburgers into her mouth like she’s hosting the world’s biggest culinary gang bang while somehow maintaining a size 2, because Cool Girls are above all hot. Hot and understanding. Cool Girls never get angry; they only smile in a chagrined, loving manner and let their men do whatever they want. Go ahead, shit on me, I don’t mind, I’m the Cool Girl.

Men actually think this girl exists. Maybe they’re fooled because so many women are willing to pretend to be this girl.”

Where Dag fails is posturing herself as being above the “candid girl” as if she has a personal vendetta against the woman herself, as opposed to the image that men have created for her. She falls into the already paved path of blaming the woman for the man’s selfish indulgence. John Berger once noted, “You painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her, put a mirror in her hand and you call the painting Vanity, thus morally condemning the woman whose nakedness you depicted for your own pleasure.”

Data Says… You’re Not Equal (Surprise!)

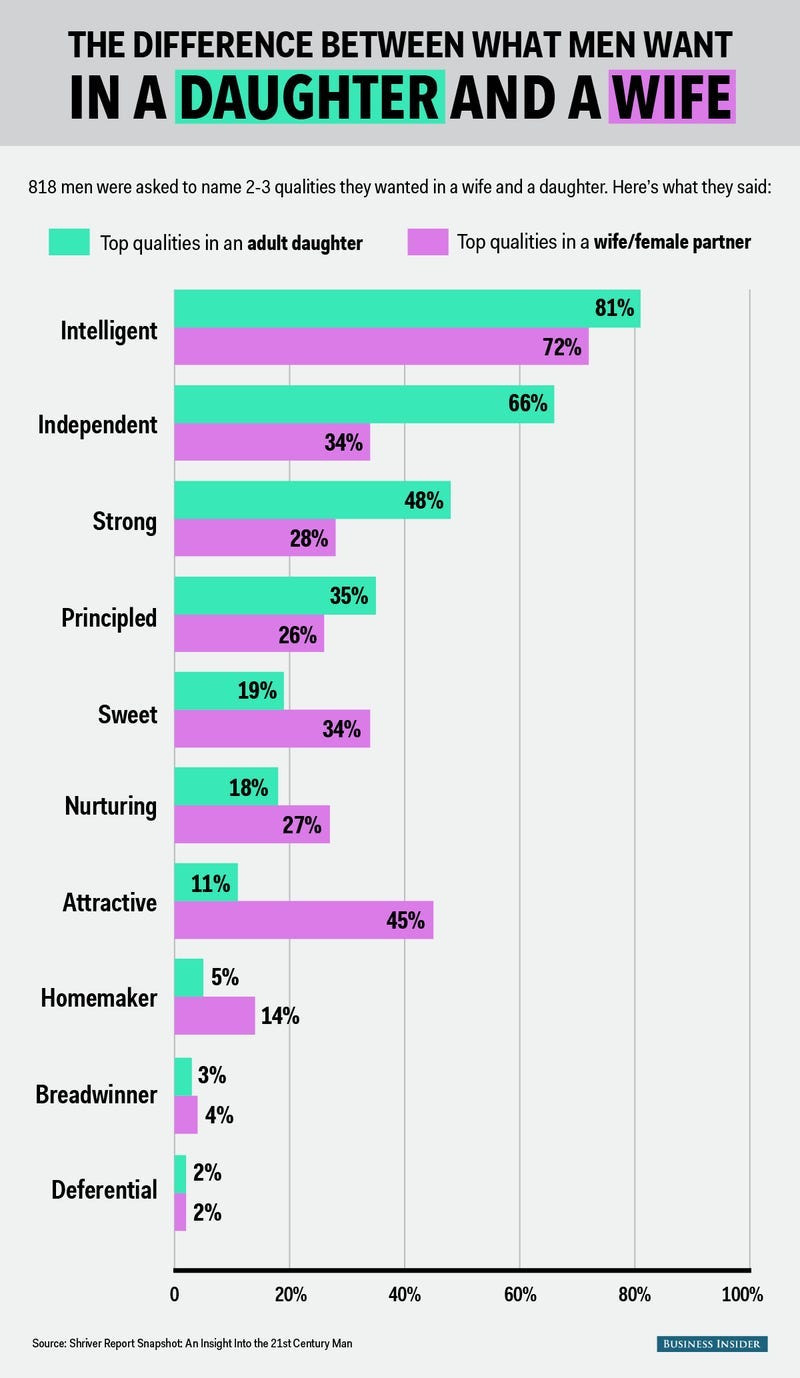

In 2015 Hart Research Associates conducted a study in which 818 men put forth stark differences in what they would prefer in their daughters versus their wives. For example, men value qualities such as intelligence, independence, principality, and strength in daughters far more than in wives. Inversely, how attractive, sweet, and a homemaker were far more preferred in wives over daughters. The study ultimately revealed that men want a submissive wife and a successful daughter. “Success” of course, equating to more masculine traits. Afterall, men see daughters as extensions of themselves, where their wives are less than equal–ideally an opposite, nurturing where they refuse to be. One can assess that men would want their daughters (the ones carrying their “legacy”) to be successful in ways they may have prevented their wives to be.

The Fate of Female-Kind

As fathers desire stereotypically male traits in their daughters whilst yearning for a wife that would just sit down and shut up, a kind of alliance is born. Now the father who is supposedly independent, principled, and strong and the daughter who is independent, principled and strong, look down on wife and mother for her more docile personality*. He fails to respect his wife because even after all her sacrifices she won’t conform, and she fails to respect her mother because she can’t imagine growing up to be so ‘feeble’. As Burstow says, “Often father and daughter look down on the mother (woman) together. They exchange meaningful glances when she misses a point. They agree that she is not bright as they are, cannot reason as they do. This collusion does not save the daughter from the mother's fate.” (Radical Feminist Therapy)

We can observe the same misguided resentment in ‘Subway Girl’. The ways in which father and daughter combine their efforts to subconsciously berate the mother mirror ‘Subway girl’ in the way that she unknowingly uses the criticism of another woman to escape her own dissection. Overall, commenting on the most arbitrary aspects to another person suggests that you’re in some way superior. It’d be easy to bet that our audacity here comes from a climate in which opinion is so often stated as fact, and where echo chambers online validate us into thinking every opinion we have just has to be shared… (said the arguably over-zealous blog writer).

Where women are concernd, we know it’s not easy to escape carefully curated notions of being simple, and so it’s no surprise that women often project this fear of being unseen onto other women. But where men are already champions in failing to conceive an independent subject, we appear to be ‘beating a dead horse’ as they say. People hate subway girl because she represents the type of woman who would rather judge than be judged, though we’re willing to bet she’s more illustrative of a lot of women than people want to admit. Privately we assume ourselves as being larger than the girl next door, the ‘candid girl’. In truth, we all represent candidness in all its shame to those men around us, and so as coin these phrases, we invertedly contribute to our own reduction. Instead we might shift our focus, coining phrases like ‘The Blind Man’ archetype or ‘The Egoist’. How embarrassing it is to have such a weak sense of observation, or such a lack of self awareness? Where this model is concerned, there’s ‘nothing in his head’...

- Alaia & Asisa

Subscribe to the incredible Asisa Kadiri! She is absolutely incredible and by far one of the most insightful and inspired writers I’ve ever had the pleasure of working with and knowing. Be sure to support her below!

Writing with you was a pleasure, as always! I look forward to more collabs in the future